Pelvic floor disorders involve a dropping down (prolapse) of the bladder, urethra, small intestine, rectum, uterus, or vagina caused by weakness of or injury to the ligaments, connective tissue, and muscles of the pelvis.

- Women may feel pressure or a sense of fullness in the pelvis or have problems with urination or bowel movements.

Pelvic floor disorders occur only in women and become more common as women age. During their lifetime, about 1 of 11 women needs surgery for a pelvic floor disorder.

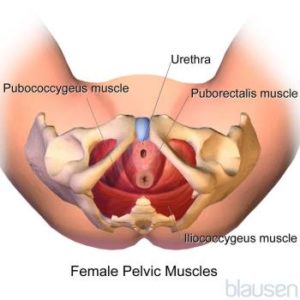

The pelvic floor is a network of muscles, ligaments, and tissues that act like a hammock to support the organs of the pelvis: the uterus, vagina, bladder, urethra, and rectum. If the muscles become weak or the ligaments or tissues are stretched or damaged, the pelvic organs or small intestine may drop down and protrude into the vagina. If the disorder is severe, the organs may protrude all the way through the opening of the vagina and outside the body.

Pelvic floor disorders usually result from a combination of factors.

The following factors commonly contribute to development of these disorders:

- Having a baby, particularly if the baby is delivered vaginally

- Being obese

- Having an injury, as may occur during hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) or another surgical procedure

- Aging

- Frequently doing things that increase pressure in the abdomen, such as straining during bowel movements or lifting heavy objects

Being pregnant and having a vaginal delivery may weaken or stretch some of the supporting structures in the pelvis. Pelvic floor disorders are more common among women who have had several vaginal deliveries, and the risk increases with each delivery. The delivery itself may damage nerves, leading to muscle weakness. The risk of developing a pelvic floor disorder may be less with a cesarean delivery than with a vaginal delivery.

As women age, the supporting structures in the pelvis may weaken, making pelvic floor disorders more likely to develop.

Having a hysterectomy also weakens the structures in the pelvis, making pelvic floor disorders more likely.

Less common factors that may contribute include accumulation of fluid within the abdomen (ascites, which puts pressure on pelvic organs), disorders of nerves to the pelvic floor, tumors, and disorders of connective tissue (the tough, often fibrous tissue that is present in almost every organ, including muscles, and that provides support and elasticity). Some women have birth defects that affect this area or are born with weak pelvic tissues.

Types and Symptoms

All pelvic floor disorders are essentially hernias, in which organs protrude abnormally because supporting tissue is weakened. The different types of pelvic floor disorders are named according to the organ affected. Often, a woman has more than one type. In all types, the most common symptom is a feeling of heaviness or pressure in the area of the vagina—a feeling that the uterus, bladder, or rectum is dropping out.

When the Bottom Falls Out: Prolapse in the Pelvis

|

Symptoms tend to occur when women are upright, straining, or coughing and to disappear when they are lying down and relaxing. For some women, sexual intercourse is painful.

Symptoms tend to occur when women are upright, straining, or coughing and to disappear when they are lying down and relaxing. For some women, sexual intercourse is painful.

Mild cases may not cause symptoms until the woman becomes older.

Prolapse of the rectum (rectocele), small intestine (enterocele), bladder (cystocele), and urethra (urethrocele) are particularly likely to occur together. A urethrocele and cystocele almost always occur together.

Damage to the pelvic floor often affects the urinary tract. As a result, women who have a pelvic floor disorder often have problems controlling urination, resulting in urine leaking out involuntarily (urinary incontinence) or problems completely emptying the bladder (urinary retention).

Rectocele

A rectocele develops when the rectum drops down and protrudes into the back wall of the vagina. It results from weakening of the muscular wall of the rectum and the connective tissue around the rectum.

A rectocele can make having a bowel movement difficult and may cause constipation. Women may be unable to empty their bowels completely. Some women need to place a finger in the vagina and press against the rectum to have a bowel movement.

Enterocele

An enterocele develops when the small intestine and the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritoneum) bulge downward between the vagina and the rectum. It occurs most often after the uterus has been surgically removed (hysterectomy). An enterocele results from weakening of the connective tissue and ligaments supporting the uterus or vagina.

An enterocele often causes no symptoms. But some women feel a sense of fullness or pressure or pain in the pelvis. Pain may also be felt in the lower back.

Cystocele and cystourethrocele

A cystocele develops when the bladder drops down and protrudes into the front wall of the vagina. It results from weakening of the connective tissue and supporting structures around the bladder. When a urethrocele and cystocele occur together, they are called a cystourethrocele.

Women with either of these disorders may have stress incontinence (passage of urine during coughing, laughing, or any other maneuver that suddenly increases pressure within the abdomen). If severe, these disorders can cause overflow incontinence (passage of urine when the bladder becomes too full) or urinary retention. After urination, the bladder may not empty completely. Sometimes a urinary tract infection develops. If the nerves to the bladder or urethra are damaged, women who have these disorders may develop urge incontinence (an intense, irrepressible urge to urinate, resulting in the passage of urine).

Prolapse of the uterus

In prolapse of the uterus, the uterus drops down into the vagina. It usually results from weakening of the connective tissue and ligaments supporting the uterus. The uterus may bulge in the following ways:

- Only into the upper part of the vagina

- Down to the opening of the vagina

- Partly through the opening

- All the way through the opening, resulting in total uterine prolapse (procidentia)